Many Happy Returns!

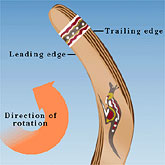

The boomerang is a bent or angular throwing club with the characteristics of a multi-winged airfoil. When properly launched, the boomerang returns to the thrower. Although the boomerang is often thought of as a weapon, the device has primarily been used in hunting and served as a recreational toy. The boomerang consists of a leading wing and a trailing wing connected at the elbow. Each wing has the typical cross section of an airfoil. Therefore, each wing has a leading and trailing edge arranged so the leading edge strikes the air first as the boomerang rotates. Due to this configuration, there are right-handed and left-handed boomerangs. A left-handed boomerang is simply a mirror image of the right-handed boomerang. The typical angle between the wings is 105 degrees to 110 degrees.

The boomerang is a bent or angular throwing club with the characteristics of a multi-winged airfoil. When properly launched, the boomerang returns to the thrower. Although the boomerang is often thought of as a weapon, the device has primarily been used in hunting and served as a recreational toy. The boomerang consists of a leading wing and a trailing wing connected at the elbow. Each wing has the typical cross section of an airfoil. Therefore, each wing has a leading and trailing edge arranged so the leading edge strikes the air first as the boomerang rotates. Due to this configuration, there are right-handed and left-handed boomerangs. A left-handed boomerang is simply a mirror image of the right-handed boomerang. The typical angle between the wings is 105 degrees to 110 degrees.

As the boomerang flies through the air, each wing produces lift. Due to the shape of the boomerang a pressure differential exists between the lower and upper surface (on each wing) which creates aerodynamic lift. A boomerang is thrown with a spin which has two effects on the boomerang as it travels through the air: a stabilizing force known as gyroscopic stability and the development of a curved flight path. The turning force imposed on the boomerang comes from the unequal air speed of the spinning wings. For a stationary, spinning boomerang, both wings would produce the same amount of lift. Now applying the same spinning boomerang with a forward velocity and the speed of the air traveling over the wings differs. Thus, the forward moving wing experiences more lift than the retreating wing. The net result is a force which turns the boomerang.